As a parent of four children who all love Lego and Duplo, I have spent many years dodging around and stepping over bricks and blocks throughout my house. To prevent injury (to myself) and damage (to the toys), I have purchased every manner of shelves, cubbies, bins, bags, and boxes to contain the mess. No matter how convenient we have made the process of putting away these pieces, the blocks still get left out, only to be put away when myself or my wife ask the kids to clean up their play area. We usually make that request before dinner or bedtime, which carries the stress of a deadline—and what results is a whirlwind of kids hastily tossing bricks and blocks into whatever container is nearest. The items end up technically stored in a container, but rarely in an organized manner. For my children, the flow of play and the outcome of their construction is their primary focus, and my goals for them to clean up afterwards fall to a very distant secondary focus.

In our work here at EA, we have the privilege of working with folks in almost every type of education organization. We see data generated from individual classroom interactions all the way up the data ladder to statewide growth metric data. My personal journey in this space started with implementing Ed-Fi for school districts as the technical architect for a collaborative of school districts housed in a state university’s school of education. We deployed an Ed-Fi infrastructure in an on-premises data center in 2018, because at the time, the core technology we were using could not be deployed in the cloud without at least a tenfold increase in infrastructure costs. Once we deployed the on-premises tech stack, the team worked with districts and staff to push data from their source systems into the Ed-Fi ODS (Operational Data Store). We learned a great deal from this process and from implementations of Ed-Fi around the country, and I would like to share about what worked, and perhaps more importantly, what did not work (and why).

Lessons we've learned

We have seen how school and LEA (Local Education Agency, or district) staff can interpret and respond to a district-wide initiative. Often, we see alignment in their view of the mission, but a difference in the execution of that mission. Staff at LEAs are constantly maintaining a balance of their own local needs with needs imposed from external sources. As a non-profit partner, we are the external source imposing a need—in this case, for them to augment their existing business processes to accommodate an Ed-Fi implementation. This is not always a natural transition, nor an especially stable one. As LEA personnel turn over and staff responsibilities evolve to meet emergent and shifting needs, the canonical understanding of what Ed-Fi is—and how to furnish data to the ODS—leaves with the staff members who are initially bought into (and trained on) the initiative. This can result in a constant need for us as the external partner to maintain that knowledge base and enable ongoing transfer to new personnel.

In some of our projects, we are also able to support districts as their state education agency (SEA) rolls out Ed-Fi to modernize state-level reporting. In these cases, we have seen the same tenuous balance between local and external needs. Even with the weight of state accountability and funding, this often still is not enough to support successful, significant changes to local practices.

For both the LEA and SEA use cases of Ed-Fi, I’ve seen a phenomenon similar to what I’ve experienced with my kids’ blocks: ODSs are eventually filled with data, but there is often little if any change to the underlying practices needed to make those data useful to all consumers of those data. Why haven’t modernization efforts managed to systemically achieve changes to data management and data governance? In most cases, SEAs, vendors, and district staff are expending equal (or more) effort than in the days before the data modernization. My assertion is that external efforts too often attempt to impose a value system and approach to interoperability that does not support the requisite change in stakeholders’ practices. Just like my children’s toy boxes were filled with bricks, the ODSs get filled with data—but the users do not yet see the value of what that system could do.

Since those early days, we have been able to start to address stakeholders’ underlying practice. This has been more tractable at the local level compared to the state level, because states often face pressure to fulfill delivery of the data, leading to different coping mechanisms to wrestle with the intrinsic complexities of the data across LEAs and reconciling it to the SEA’s needs. One of these coping mechanisms can take the form of vendors deploying complex proprietary code to accommodate existing district practices. Another involves districts making changes to their source data to satisfy the demands of the state validations for reporting. These band-aid solutions take the suboptimal practices from flat file transfers and apply those same strategies to the “modernized” approach.

Using our learnings to improve

So where do we go from here? With my children, we had to go beyond just providing more storage and organization options. We had to take time to understand what they spent a lot of time doing (their existing practice) to learn what would speak to their needs (their goals). We learned that they lost a good amount of play time while searching for bricks of certain colors and for specific connectors. We revised our approach to now sort assorted styles and colors of Legos into specific bins, organized by the most-played-with pieces. This resulted in fewer boxes being pulled out, leading to fewer bricks being pulled out, which led to fewer bricks having to be put away. Direct communication with them and alignment of our goals to theirs led both sides to a productive and ongoing solution. Could we take this small-scale example and use it as a model for solving the challenge of rolling out Ed-Fi at scale? I say yes!

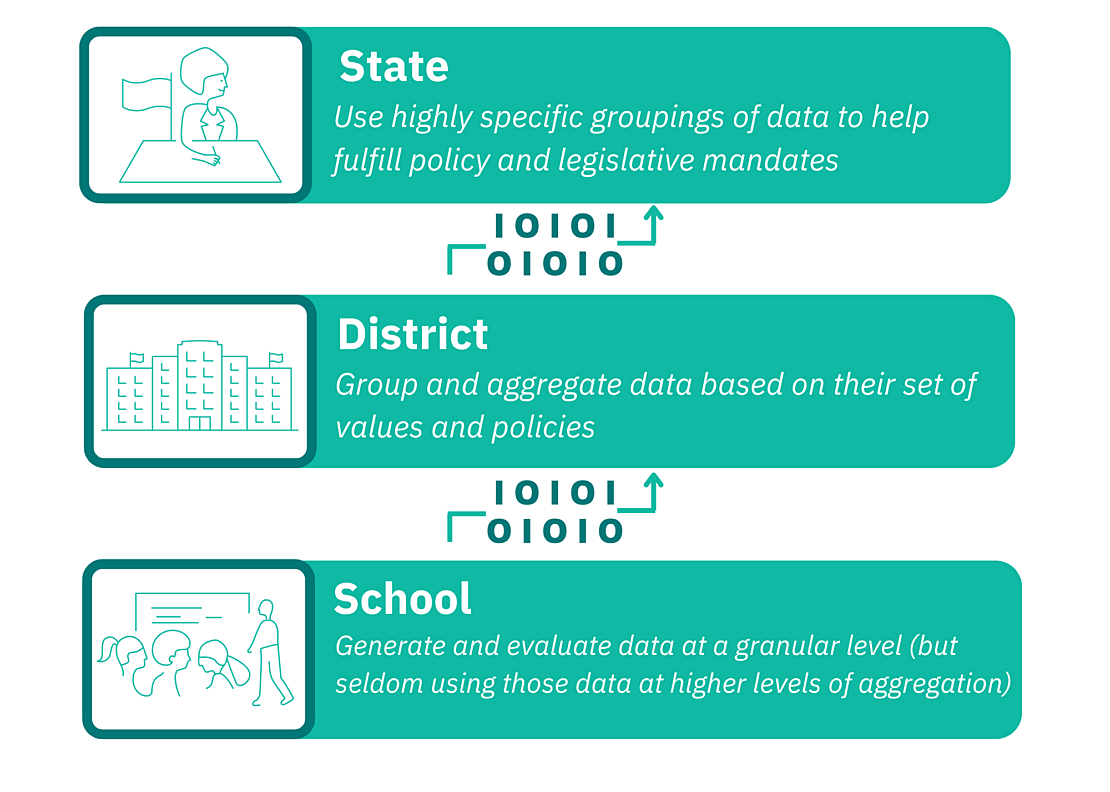

In our work, we have identified three key parties who need to be engaged and brought together to achieve a successful, wide-scale Ed-Fi implementation. Let us start with the school level and identify some needs and processes. School-level staff and students generate granular data, like daily attendance and course enrollment. School administrators then coordinate with school staff to group those granular data together, and then they plan and execute action based on patterns seen in that grouped data. Even with modern student information systems (SIS), school staff and leaders spend hours each week assembling data into formats that work best for them and their needs. Their context is the classroom- and building-level needs of their students.

If we move up a level to district administrators, there is yet another set of values and policies that drive the grouping and aggregation. A superintendent may be interested in district-wide inequities in discipline data, and they may want compiled disproportionality measures grouped by race and ethnicity, or by other demographic measures. We have often seen requests from district and school administrators to provide aggregate counts by specific student characteristics or program participation so they can complete grant applications. Finally, at the state level, we have highly specific groupings of data needed to fulfill policy and legislative mandates. States often take those same aggregations or groupings of data from the districts and draw conclusions about policy adherence—and in many cases, they may further refine state policy based on those data being surfaced.

What happens at each level parallels our Lego blocks scenario, in that each group has a set of values that matter mostly within the group. Even if the underlying data are the same, each manipulation of the data to meet specific goals or attain certain outcomes at any one level can obscure or distort the reality that the data are meant to capture. The further “up” you move, the more the data shifts from being a snapshot of day-to-day reality to being a painting inspired by reality.

An opportunity to change the paradigm

Why does Ed-Fi present an opportunity to change this paradigm? It can serve as a forcing mechanism for each level of the system to come to terms with the actual granular data themselves—rather than just focusing on the grouping of data they are most comfortable with. If all three groups identified above started with examining the creation of granular data and what data practices exist at that level, they would see a complex web of motivations, including “this is how we’ve always done it” and “we’re not sure why we do this,” along with relics of past administrations and leadership. Unwinding these granular data practices and replacing them with sound approaches to data management and creation is a major component of a successful Ed-Fi implementation. An activity like mapping local codes (such as for students’ gender or race) to Ed-Fi descriptors can be an opportunity for different stakeholders to critically examine why certain codes exist and what their utility is. This task can then allow for efficiencies at the school level. In examining the codes, the school and district administration then can align their intended policy with their actual practice, and in turn, they have assurance that the day-to-day data creation will yield the information that reflects reality. At the state level, supporting the methodology of selecting and mapping codes allows for policymakers to see the complexities and bureaucratic burdens often placed on the LEA, and ideally, this can then inform state-level policy that enhances the classroom experience for teachers and students.

As a community, we are at an inflection point where cloud technology has allowed for affordable deployments of massive data systems. Gone are the days of high-cost on-prem implementations—but we have not systematically reallocated those cost savings to invest in the non-technical changes in stakeholders’ practice that are necessary to realize the promise of modernized data infrastructure. Here at EA, our Ed-Fi infrastructure is named StartingBlocks. That name aims to convey the importance of framing and positioning the technology early on, as it relates to long-term goals for data system modernization. To accomplish those long-term goals, our team focuses heavily on the “why” of Ed-Fi rather than exclusively on the now streamlined and cloud-based “how.” We strive to be a partner that connects the dots between vendors, practitioners, leadership, and policymakers by talking to each party and facilitating the building of bridges early in the process. Clear and open communication about challenges and roadblocks are important in setting the tone for the implementation; then, the policy and practice overhaul is the actual meat of this work. While our infrastructure is well designed and affordable, that alone is not enough. We want that infrastructure to be a force that enables the social and policy changes necessary for students to thrive, educators to feel supported, and for policymakers to refine policy with thriving students in mind.